預估價格

TWD 34,200,000-57,000,000

HKD 9,000,000-15,000,000

USD 1,184,200-1,973,700

成交價格

TWD 45,925,926

HKD 12,400,000

USD 1,593,830

簽名備註

簽名左下:荼九六

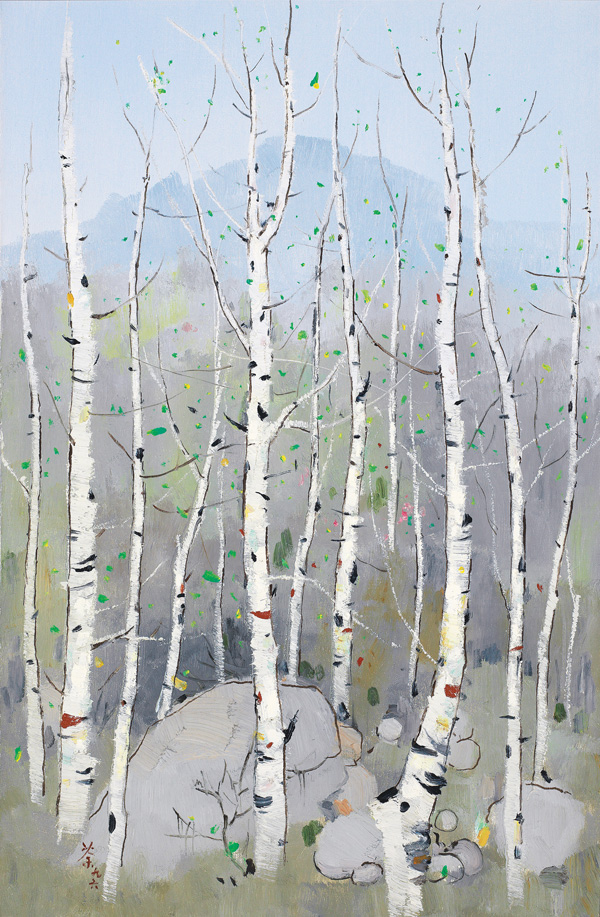

簽名畫背:北國春(白樺) 吳冠中1996

簽名畫背:北國春(白樺) 吳冠中1996

圖錄:

《吳冠中全集4》,湖南美術社,長沙,2007,彩色圖版,頁144

+ 概述

吳冠中: 斯人已去,情意永存

每一年總要發生或者感受一些事情是跟他有關的,無論是畫還是文。畫裡有夢有喜有情;文裡有思有憂有言。但是2011年,再也無法更新這個人的動態,剩下的只有舊聞和不斷更改的數字:原本就屬高價的拍賣成績,如今只可能越來越高。他就是2010年去世的吳冠中,二十世紀中國現代繪畫的代表畫家之一。

吳冠中生於江南水鄉,下筆優美、抒情,洋溢著生機和活力,即使是在他年輕時最困頓的時刻,也從未更改此種畫風。正如評論家蘇利文所寫到的:「他輕鬆自由地與自然和諧共存。」他對江南的記憶,甚至在北京已經居住了六十年,鄉音仍然未改。很多時候,他會在聊天的過程中停下來問一句:「我說的話能聽懂嗎?」

這位從解放後就不斷被「改造」的藝術家,始終保持著他的執著,他說:「我絕不向庸俗的藝術觀低頭,我絕對無法畫虛假的工農兵模式。」1979年,在中國美術館舉辦了個人畫展的吳冠中,在當年的文代會上當選為中國美協常務理事。第一次理事會上,吳冠中對「政治第一、藝術第二」開火,整個會場鴉雀無聲,無人敢接回應。他的每一次筆墨都無異於是一次現代藝術的觀念革新,從某種程度上說,他是中國現代藝術的啟蒙者。盛名之後,他仍然止不住對藝術現實的批判。「畫家走到藝術家的很少,大部分是畫匠,可以發表作品,為了名利,忙於生存,已經不做學問了,像大家那樣下苦工夫的人越來越少。」「整個社會都浮躁,刊物、報紙、書籍,打開看看,面目皆是浮躁;畫廊濟濟,展覽密集,與其說這是文化繁榮,不如說是為爭飯碗而標新立異,嘩眾唬人,與有感而發的藝術創作之樸素心靈不可同日而語。」

在《我負丹青》的書籍中,他坦承下輩子不當畫家:「越到晚年我越覺得繪畫技術並不重要,內涵最重要。繪畫藝術具有平面侷限性,許多感情都無法表現出來,不能像文學那樣具有社會性。在我看來,一百個齊白石也抵不上一個魯迅的社會功能,多個少個齊白石無所謂,但少了一個魯迅,中國人的脊樑就少半截。我不該學丹青,我該學文學,成為魯迅那樣的文學家。從這個角度來說,是丹青負我。」

他堅持批判的文化品格和美學主張—對意境和其清新、明朗自然風格的藝術追求,有種相馳又相應的協調。吳冠中一直在研究中、西繪畫異同的基礎上尋找兩者的結合點,他將傳統水墨的寫意和西方現代表現性繪畫融會貫通,這種東西交融的技法使得他的作品具有明快,單純的現代性,同時又不失中國式寧靜、抒情的詩意。

在其一生的創作題材中也無不體現著他對中國式寧靜、抒情詩意畫面的美學追求,其作品多集中在江南、北國、水鄉、動物等題材。

其目前名列前十名的拍賣紀錄皆是此類作品。2010年的《長江萬里圖》成交紀錄人民幣5712萬,2009年《鸚鵡天堂》人民幣3025萬,《北國風光》人民幣3024萬。此幅創作於1996年的《北國春》同樣屬於此類代表風格。以簡單的構圖,淡墨的筆法,素雅的配色,將北國春天中素雅而又爛漫初現的特點躍然紙上。

溫暖北國

出生於江南的吳冠中,對北國有著不同的情感。北國多用來代指北方的景色。吳冠中在作品中反覆表達對北國風景的眷戀。所有的風景無不盡顯詩意。這種詩意和情感和他在北國的經歷形成了強烈的反差,他從未因其經歷過的苦難而在畫面中形成過任何慘澹的畫面,總是一如既往的淡然、溫婉。像他的人,更像他畫中的樹木,即使是一株株的小樹,也自有它筆直的身姿,融於自然,同時又超越了周邊風景。

1970年,吳冠中被下放河北農村,受盡苦難,包括畫畫的權利也被剝奪。即使在幾年後偶爾可以畫點畫,仍然無法獲得材料。他在70年代創作了一批幾十釐米見方的小作品,都是他買了一塊多錢一個的簡易黑板,刷上膠,直接在上面畫油畫的創作;畫架乾脆借來房東的糞筐代替。這是後來吳冠中一度被大家戲稱為「糞筐畫家」的來由。

除了不能畫畫,更痛苦的是,吳冠中夫婦和三個孩子,一家五口分離在五個地方,老大在內蒙,老二在山西農村,老三在建築工地,經常變動地址。吳冠中夫妻倆分別在兩個農場,很難見面。在此過程中吳冠中飽受肝炎折磨,還罹患其他惡疾。在這種殘酷的生活境遇中,吳冠中只有拼命地畫,在畫畫中忘卻或者乾脆在繪畫中死去,反倒是一種美好的宿命。匪夷所思的是,他的肝炎在瘋狂的繪畫中不藥而癒了。正是因為這段經歷,吳冠中的筆下常常充斥著高粱、玉米、冬瓜、石榴、樺樹、石頭、野花等自然田野之光。吳冠中如此評價自己的選材,「我有兩個觀眾,一是西方的大師,二是中國老百姓。二者之間差距太大了,如何適應?是人情的關聯。我的畫一是求美感,二是求意境,有了這二者我才動筆畫。我不在乎像和漂亮,那時在農村,我有時畫一天,高粱、玉米、野花等等,房東大嫂說很像,但我覺得感情不表達,認為沒畫好,是欺騙了她。我看過的畫多矣,不能打動我的感情,我就不喜歡。」

人品、藝品

吳冠中生前便對社會給予了慷慨的捐贈,無論是數量還是作品的精彩程度,價值都非常之高。從二十世紀至今,只有他和徐悲鴻做到了這一點。據不完全統計,徐悲鴻直接義賣捐出去的錢款高達數億元,死後更是將所有作品捐贈給了國家;吳冠中年近九十歲,眼見自己的作品在拍賣市場行情越來越高,自己一輩子居住在幾十平方米小屋內,生活簡樸,選擇了向社會捐贈了數百幅價值連城的名作的方式完成自己對家、國、藝、品這人生幾大主題的抒寫。

正是因其人品的難得,藝品的高超,即使在金融危機之時,其作品價格依然如前,不斷創造新的紀錄。所謂大家和畫匠的區別,有時候就在文化品格和人品的差異上顯出不同和高下。而這種差異最終又會作用到畫面上,形成作品核心價值的不同。對於收藏者來說,有時候買下的不僅僅是一幅畫面,一件作品,更是一種人心,一段佳話,一次共鳴。

相關資訊

現代與當代藝術

羅芙奧香港2011春季拍賣會

2011/05/30 (一) 上午11:30